HYPOMAP: AI Helps to Map Out the Brain’s Hunger Center for First Time

Researchers at the University of Cambridge (UK) have mapped the human brain’s appetite center for the first time. Scientists believe this could unlock new targets for safer, more effective obesity treatments.

The cellular atlas, which researchers are calling HYPOMAP, captures over 430,000 neurons in the human hypothalamus— the area of the brain that regulates feeding behavior based on hunger and fullness levels.

Genetic mutations in hypothalamic cells can disrupt the normal patterns of hunger and satiety signals, potentially causing some individuals to experience more heightened and more frequent hunger, increasing their susceptibility to obesity.

We had the privilege of interviewing Giles Yeo, the senior author and lead researcher behind the development of HYPOMAP. Our conversation provided deeper insight into the study’s findings, the challenges of researching the human hypothalamus, and the potential impact of this work on future obesity treatments.

Researchers Know Surprisingly Little About the Human Mechanisms of Hunger

A recent study published in Nature presents HYPOMAP, a comprehensive cellular atlas of the human hypothalamus. This study aims to shed light on the human hypothalamus structure, a previously understudied brain region, as most research has historically relied on rodent models.

“Most of what we know about the hypothalamus has come from studies in mice and may not fully translate to humans.” senior author Giles Yeo, tells us.

The large knowledge gap exists because studying a live human brain in detail is extremely challenging. Unlike other organs, it cannot be biopsied or extensively examined without causing significant harm, severely limiting direct research on its inner workings.

“It is impossible, let alone unethical, to get into the brain of a living human being,” says Giles. “So, we know most of the hypothalamus’s molecular details from mice.”

While studying animal brains has been essential for understanding the neural mechanisms behind obesity and developing treatments like semaglutide, it also limits scientists’ ability to identify human-specific targets that could lead to safer , more effective weight-loss therapies.

HYPOMAP Could Help Scientists Discover Better Obesity Treatments

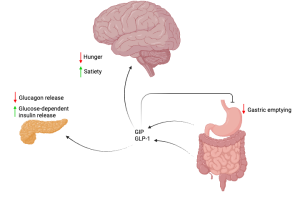

Current therapies on the market, such as semaglutide and tirzepatide, target receptors throughout the body, particularly in the hypothalamus and pancreas. The effect that these receptors have when activated will depend on their location.

For example, pancreatic cells are stimulated to release insulin for glucose metabolism, and hypothalamic cells boost the fullness signal in the brain.

Semaglutide exclusively mimics a hormone called Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 (GLP-1), which targets the GLP-1 receptor (GLP-1R), while tirzepatide targets both GLP-1R and another receptor, called glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) receptor.

Semaglutide exclusively mimcs the action of GLP-1, mostly released from cells in the large intestine. Tirzepatide mimics both GLP-1 and GIP, the latter of which is primarily released from an early section of the small intestine. Diagram created in https://BioRender.com.

These medications have been game-changing for patients with type 2 diabetes and those needing assistance with weight loss, but they don’t work for all patients and can even cause intolerable side effects.

“Maybe 5–10% of people still don’t respond to the drug. We don’t know why.” says Giles.

Side effects are another problem, with one of the most common adverse events, nausea, reported in up to 50% of patients. On top of this, complications such as pancreatitis, gastroparesis, or cholecystitis are rare, but nonetheless serious, concerns.

For patients suffering from severe symptoms, they will likely discontinue treatment and thus would need an alternative.

HYPOMAP Could Establish Alternative Targets for Intolerant or Unresponsive Patients

So how could scientists benefit from HYPOMAP?

Since this is the first time that scientists have been able to capture a map of the human hypothalamus, creating similar maps based on obese or underweight individuals could highlight important genetic differences between the different body mass indexes (BMIs).

This could be used to improve the therapeutic landscape of obesity treatments in two ways:

- Find alternative medicines with completely different targets.

- Combine a lower dose of a pre-existing GLP-1 medication with a novel therapy that has a different target, reducing the risk of side effects associated with the full dose.

In fact, this second strategy is currently being tested by Novo Nordisk, who launched a clinical trial in December 2024, investigating the potential of treating overweight individuals with CagriSema – a drug that combines cagrilintide and semaglutide into one.

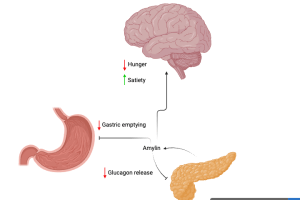

Cagrilintide boosts the effects of semaglutide by mimicking a different hormone, called amylin, which is produced by the pancreas after a meal to stop glucose production and slow the movement of food through the gastrointestinal system (see diagram below).

Cagrilintide mimics amylin, produced in response to rising blood sugar level. Amylin acts on the stomach to slow down gastric emptying. In the pancreas, amylin inhibits the release of glucagon. Diagram created in https://BioRender.com. Adapted from D’Ascanio AM, Mullally JA & Frishman WH. Cardiol. Rev. 2024;32(1):83-90.

HYPOMAP could help uncover more synergistic drug targets while also identifying candidates likely to produce unpleasant side effects. For example, researchers can use HYPOMAP to pinpoint specific receptors on certain cell populations that should be avoided in treatment development.

HYPOMAP Reveals New Gene Linked with Obesity

Using HYPOMAP, researchers identified key distinctions between mouse and human brains. Notably, they discovered that in the human hypothalamus, GLP-1 receptors with leptin receptors are present on the same cells, whereas in mice, these receptors are found on separate cells.

What’s more, the team used HYPOMAP to identify a newly-linked gene associated with an increased risk of obesity: COROA1. Whilst its role in regulating feeding behavior remains unclear, previous research has established its involvement in the immune system.

Giles speculates that COROA1 could similarly coordinate immune activity in the brain to protect against neuroinflammation, a phenomenon that is known to contribute to both obesity and neurodegeneration:

“People with reduced functionality of this gene are predisposed to a higher BMI. But we don’t know why this is the case.”

Giles emphasizes that this is an area of research that requires further investigation.

Building a Map of the Hypothalamus Using a Concoction of Human and Computational Methods

So, this begs the question: Why is this the first time such an undertaking has been done, and how did they go about developing HYPOMAP?

They started with the brain tissue of eight healthy BMI donors, obtained across six UK brain banks: The Edinburgh Brain and Tissue Bank, MRC London Brain Bank for Neurodegenerative Diseases, Cambridge Brain Bank, Southwest Dementia Brain Bank, Parkinson’s UK Brain Bank and University of Leipzig Medical Centre Institute of Anatomy.

Then, the team performed single-nucleus RNA sequencing (sn-RNA seq), a process where genetic information is extracted from a specialist compartment in cells, called the nucleus. This method is compatible with frozen tissue rather than live tissue, which is essential when using brain bank donor samples.

Individual genetic information was combined into one dataset and corrected for any technical errors. To do this, the researchers used single-cell Variational Inference (scVI), a deep-learning framework designed to denoise complex data by identifying and retaining key underlying patterns.

Once integrated, the group clustered and annotated cells using a mixture of manual, statistical, and machine-learning methods. This enabled them to categorize cell types based on gene expression, helping to group populations of cells in the hypothalamus.

Another crucial step was to map out the genetic profiles of cells to their 3D spatial arrangement. With the help of a machine learning tool called cell2location, they combined sn-RNA-seq data with spatial transcriptomics data. Since spatial transcriptomic has a lower resolution than sn-RNA-seq, merging the two enables scientists to pinpoint where cells are in the hypothalamus at a high resolution.

Concluding Remarks and Future Perspectives

While this study captures the human hypothalamus atlas statically, it would be useful to see how gene patterns change across different BMIs. We asked Giles what’s in store for the future of HYPOMAP.

“We’re currently working on understanding genetic changes to the hypothalamus in underweight and obese states,” says Giles.

However, to track dynamic changes to gene expression in hunger signals, researchers will still need to use rodent studies. For example, if they find a specific gene that is more prevalent in obese individuals, they can directly alter the gene in mice to see the effects on feeding behavior.

This can help determine how a specific gene influences the development of obesity, potentially indicating useful drug targets.

Giles iterates this: “If we can see gene X goes up or down in obese individuals, we can ask the question: What happens if we disrupt it? What happens when we turn it on or off? Then we have to go back to mice.”

HYPOMAP marks the first time that scientists have been able to comprehensively map out the human hypothalamus, capturing thousands of cells’ genetic profiles in their preserved spatial environment.

In the future, it will be interesting to see how safer or perhaps more effective drug targets are discovered, in line with increasing awareness of this fundamental hunger center.